Vac forming made easy

Thursday, 19th January, 2017

Few techniques are more valuable when scratch building model aircraft than vacuum forming styrene sheet. Yet many model makers, myself included, have been put off both by fear of the unknown and the perceived need for specialist and costly equipment. Even when articles started to appear in the modelling press about homemade vac boxes, these seemed beyond my limited time and ‘engineering’ know-how. So when I began scratch building WW1 subjects in 1:24 scale, and throughout the mammoth project that was my first 1:5 scale Spitfire, I continued to assiduously avoid vac forming.

Then came my big P-51D and a whole new set of challenges, and I was forced to accept the inevitable: for some jobs vac forming is the only one practicable solution!

Enter my friend Bill Bosworth, the master scratch builder from North Carolina, whose beautiful models from the inter-war years – that golden age of commercial aviation – are renowned worldwide. In a couple of emails, Bill convinced me that not only is the process simple, but so is the kit needed to create creditable vac formed parts!

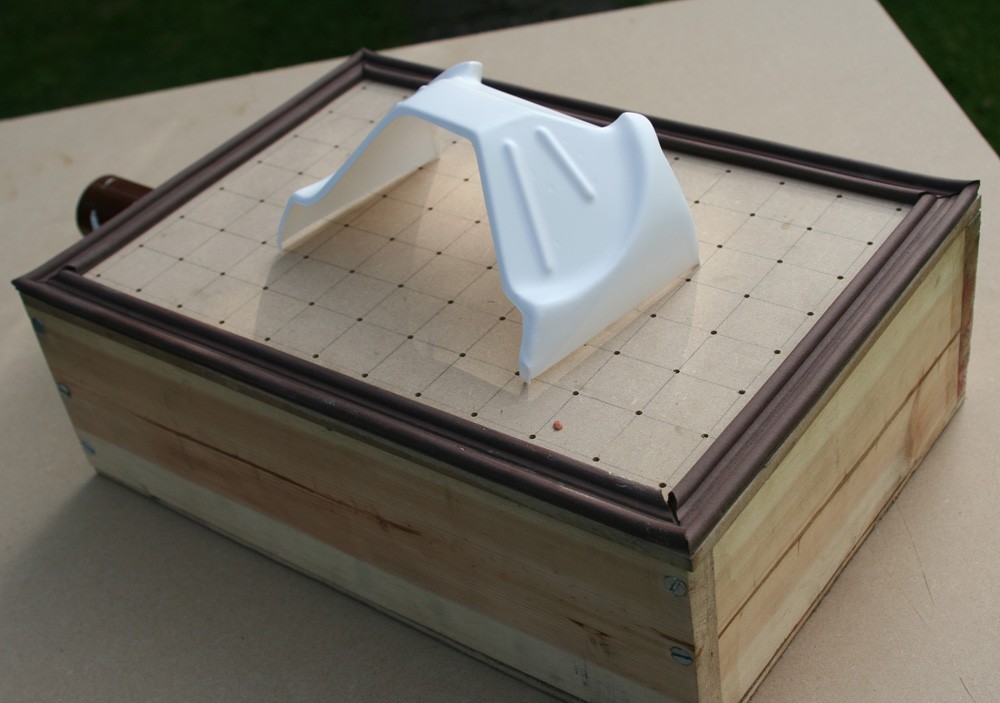

So, putting credit where it is due, I have obtained Bill’s permission to use and paraphrase extracts from his notes. The pictures are mine, and they show the box that I built in a single afternoon for less than £25. The only other requirements, apart from the ability to carve reasonably accurate wooden patterns, are access to the kitchen oven and a domestic vacuum cleaner. Bill begins with some thoughts on pattern making…

Patterns

I no longer make my patterns from hard woods, which are expensive and unnecessary. Plastic can’t tell the difference between mahogany or much softer, easier to carve woods. I use basswood almost exclusively, or even pieces of 2 x 4-in. pine. All that matters is that the pattern holds its shape for the few seconds the plastic covers it!

Normally, a pattern should have a slight undercut (e.g. to delineate its baseline), and it should be raised well above the vac-box table since the plastic will want to flare out as it is drawn down, rather than go straight down and under. It is also advisable, and especially where there are tight concave curvatures, to drill some very small holes (using say a No. 59 or 60 drill bit) all the way through the pattern to ensure the plastic pulls down tightly and evenly over the entire surface. The resulting piece will have some very small dimples, but these are easily removed with light sanding.

It is also worth remembering that when using ‘male’ patterns the sharpest edges and detail end up on the inside of the piece. This works fine for 90 per cent of jobs, although they do require a slightly undersized pattern and more attention to restoring the edges and detail.

The vac box

The basic box is screwed together from quarter-inch pine, with a silicon sealer injected along all internal joints to make them airtight. The top is 1/4-in. Masonite (I used MDF) that has been drilled with a pattern of holes. The thicker the top the less likely it is to sag under vacuum, and I usually centre an inch-by-inch vertical support beneath the top to ensure that it will not flex.

A hole has to be cut into one side of the box to accept a short length of plastic tube by which to connect the vacuum cleaner. The tube is simply glued in place, caulked with more silicone sealer and reinforced with Duct Tape.

Self-adhesive weather strip of the kind used to seal domestic doors and windows makes the top-seal. And the frame that holds the plastic sheet is made from 3/4 x 3/4-in. pine glued and screwed at the corners. Books usually specify an aluminium frame with all sorts of fasteners, from wing nuts to clamps to hold the plastic to the frame. I use Duct Tape instead … simple, cheap and fast, yet still capable of retaining a good seal!

The materials and process

Sheet styrene is cheap and readily available from all good model making and plastic materials suppliers. I keep a stock ranging from 10 thou of an inch thick to 80 thou, but I almost always use 40 thou, which holds its shape and is very easy to work with.

Over the years I have built a range of vac-boxes of different sizes. I simply cut my plastic sheet to fit and Duct Tape it securely around the entire periphery of the frame, overlapping the tape by about an inch in from the edge of the plastic. The box is connected to the vacuum cleaner using more Duct Tape, and the oven is switched on at a temperature of 125 to 150 degrees.

By placing the frame on two wooden blocks it is possible to watch it from beneath as it heats. As soon as the plastic begins to sag slightly, the vacuum cleaner is switched on and, using oven mitts, the frame is swiftly transferred from the oven to the box, ensuring that it is pressed firmly and positively down onto the airtight seal. The plastic is drawn down tight over the pattern, and within ten or fifteen seconds it will have cooled and the vacuum cleaner can be turned off.

The old “put it in the oven” method is easy and it always works. However, over the years I have found that it can take too long and be difficult to control. So now I simply move the plastic back and forth about a foot above the gas (or electric) burners of the stove. It works for me, though it takes a bit of experience to detect just when the plastic has reached the ideal temperature. When it droops just enough to flex back and forth when shaken is a good indicator, and it really doesn’t take long to discover just when this point is reached.

And a final thought… Never be afraid of ‘screw ups’. They will ALWAYS happen, no matter how many years’ experience you have, because they are part of the process and the learning curve. The main thing is to give vac forming a go!