Retrospective: The elevators

Sunday, 11th January, 2015

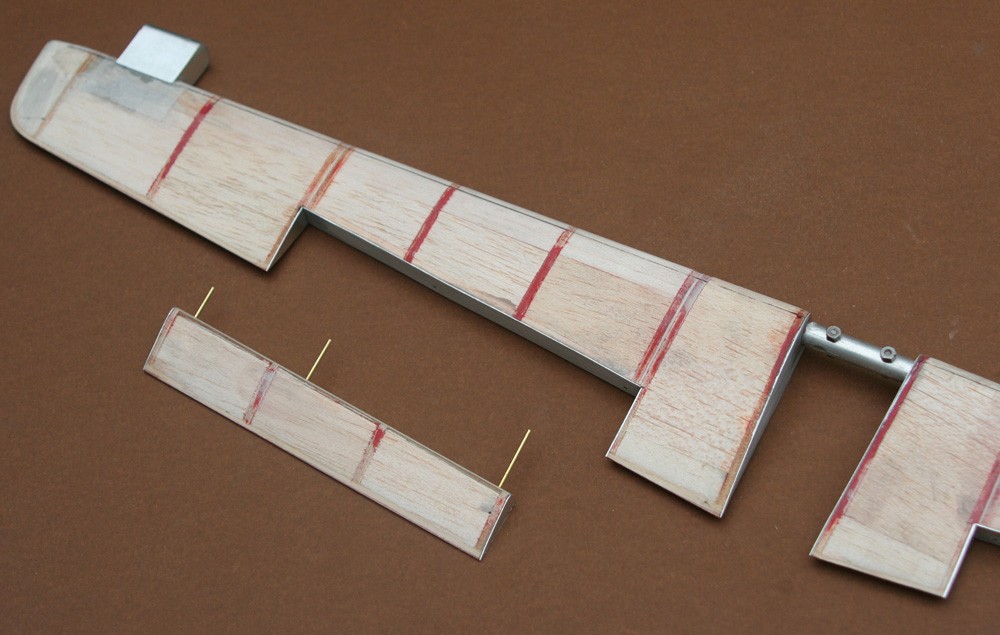

One obvious difference between the Mustang’s rudder and its elevators is that the latter are metal covered; but, in modelling them (as photo 1 shows), they are very much alike under the skin. A less obvious difference is that the elevator leading edge is substantively thicker than the horizontal stabiliser’s trailing edge. This is also apparent in the picture.

Work begins with the elevator and tail plane sheets pinned to the baseboard while the spar-like stiffeners and plywood half sections are glued on. I use viscous superglue for this because it is strong and ‘grabs’ very quickly. Brass attachment tubes are also incorporated into the structure at this stage. They guarantee that the parts can be reassembled precisely by means of snugly telescoping brass rods.

Photo 2 shows the balsa blocking operation, for which I use PVA wood glue, or similar. The two hardwood strips delineate the trim tab leading edge, and the slight gap between them is there to guide the fretsaw blade when the tab is cut away. Once the entire surface has been in-filled with balsa, the assembly can be removed from the baseboard and the process repeated on the reverse side.

With all the balsa blocking completed, and the elevators cut free by running a fine-tooth saw blade through the six embedded brass attachment tubes, both parts can be sanded roughly to shape. This is about the stage reached in Photo 3, taken just before the trim tabs were cut away. The paint on the ply cross sections is there to aid the final sanding; when the red colour begins to dissapear it is time to stop!

As the picture shows, there is still a web of plywood joining the two elevators, which cannot be removed until the torque tube has been implanted. I made it from two 6-8-in. lengths of half-round aluminium bar glued and bolted to the structure. Only with this done is it safe to remove the excess ply without risk of twisting or distortion of the completed assembly (Photo 4).

By this tage a lining of aluminium skin has been glued into the trim tab openings, over the inboard ends of the elevators and around the counterbalance weights (Photo 5 and previous blog). The trim tabs have also been sanded to the aerofoil shape at their leading edges, a process aided by the aforementioned hardwood strips.

Metal skinning starts with the trim tabs and the corresponding narrow strips along the elevator trailing edge. As explained in my description of the rudder tab, I use 0.006-in. litho plate for this. The metal is pre-folded to a knife-like trailing edge and applied in one piece. Next comes the leading edge skin. Here I revert to the normal 10 or 11 thou litho plate and form the curvature in the dry state before applying glue. Finally the main skin panels are cut and glued into place so they overlap the previously applied skin fore and aft.

Due to their shape, the elevator tips posed special problems, and a different approach: I glazed the balsa substrate with very thin superglue to ‘harden’ it and applied the skin in the form of pewter sheet, one piece for the top and one for the underside. The first sheet is left slightly oversize around the mid-line, so that the other overlaps by an equivalent amount. Once moulded to shape with fingers and thumbs, or with a soft balsa pad, the two pewter skins are applied with contact adhesive, reinforced by a careful trickle of thin superglue where they join. The metal is so malleable that any slight ridge where the top and bottom halves lap can be burnished out with a hard wood dowel.

Photos 7 and 8 illustrate the part of the job that I really enjoy. Fine detail such as the collared screw fasteners behind the counterweight and the little inset bolt bring the surface to life – and so does the riveting. I’ve described the latter process in detail elsewhere on this website; suffice it to say here that I used 1/16-in. aluminium rivets for the trailing edge skin and 3/32-in. elsewhere. The protruding shanks are clipped off and carefully sanded almost flush with the skin, leaving very neat rows of ‘flush head rivets’.

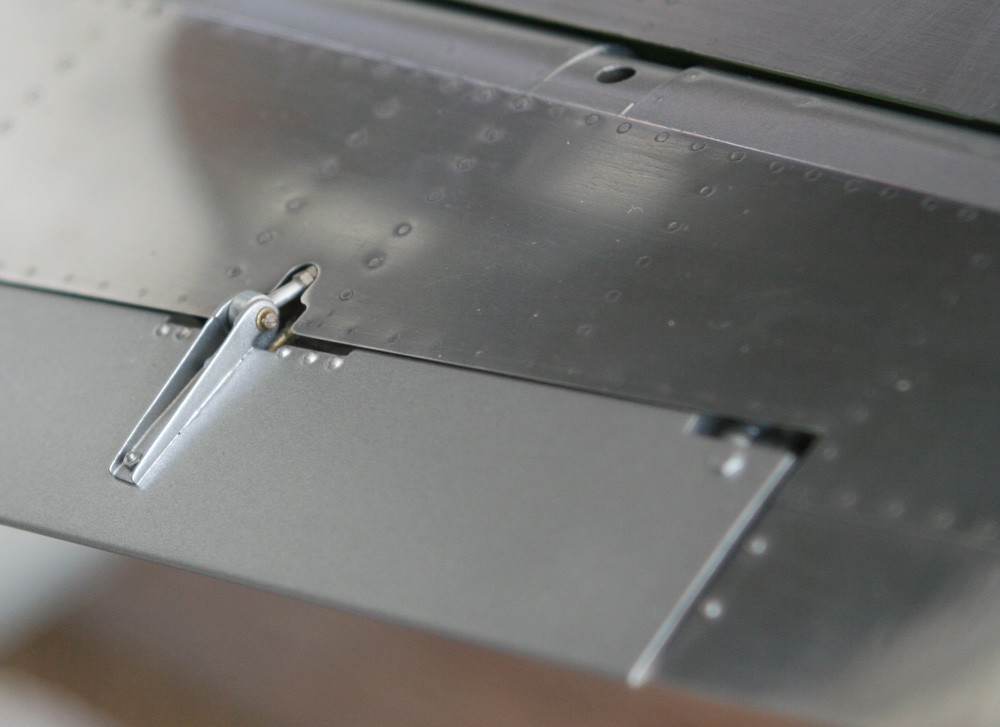

Trim tab linkages (Photos 10 and 11) are located on the upper surface of the starboard stabiliser and on the lower side to port, and they are made much as described for the rudder. Because they are clearly exposed through openings cut into the leading edges, the trim tabs hinges have to be included, albeit as dummies (which is why the attachment tubes are offset from the actual hinge positions).

Each ‘hinge’ is a short length of aluminium tube flanked by 12BA stainless steel washers. A 14BA steel bolt, nut and two tiny washers hold the three pieces together. The tube is drilled at right angles for a 1/16-in. brass pin by which the entire assembly is fastened to the elevator. It’s a ridiculously simple ruse, but it works well enough (Photo 9).

Finally a word about the finish: The attractive high polish on the aluminium skin comes at the price of hours of hard and painstaking work, down through the grades of wet and dry paper and finally with aluminium polish. It is a process that cannot be rushed. The full size machine at Hendon has its elevator leading edge, trim tabs and tips sprayed in a characteristic silver-grey and this in turn necessitates an acid etch primer coat. The end result is well worth the effort.

Previous post

Retrospective: Rudder framework

Next post

Retrospective: The flaps