First internal skin panels

Wednesday, 23rd October, 2013

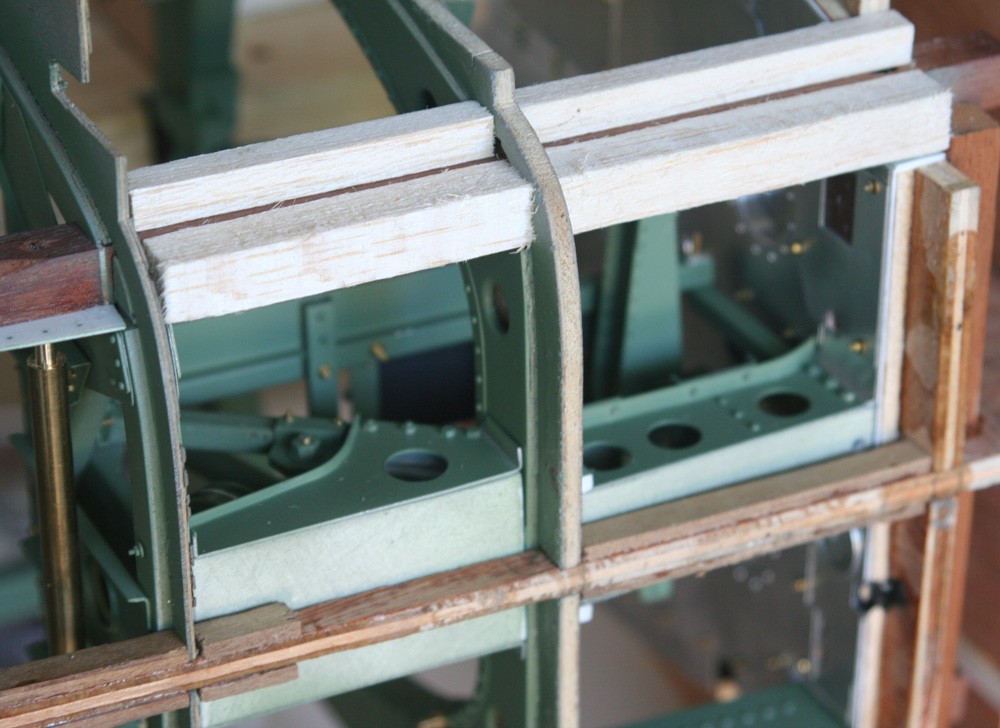

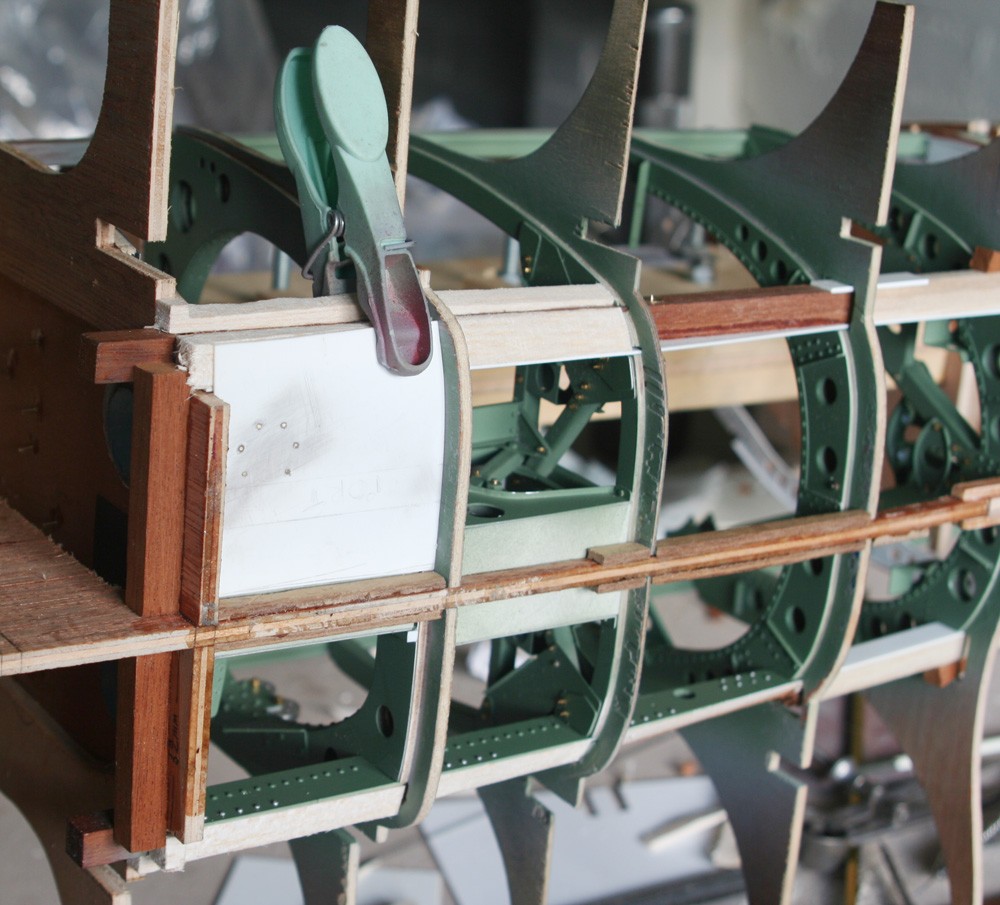

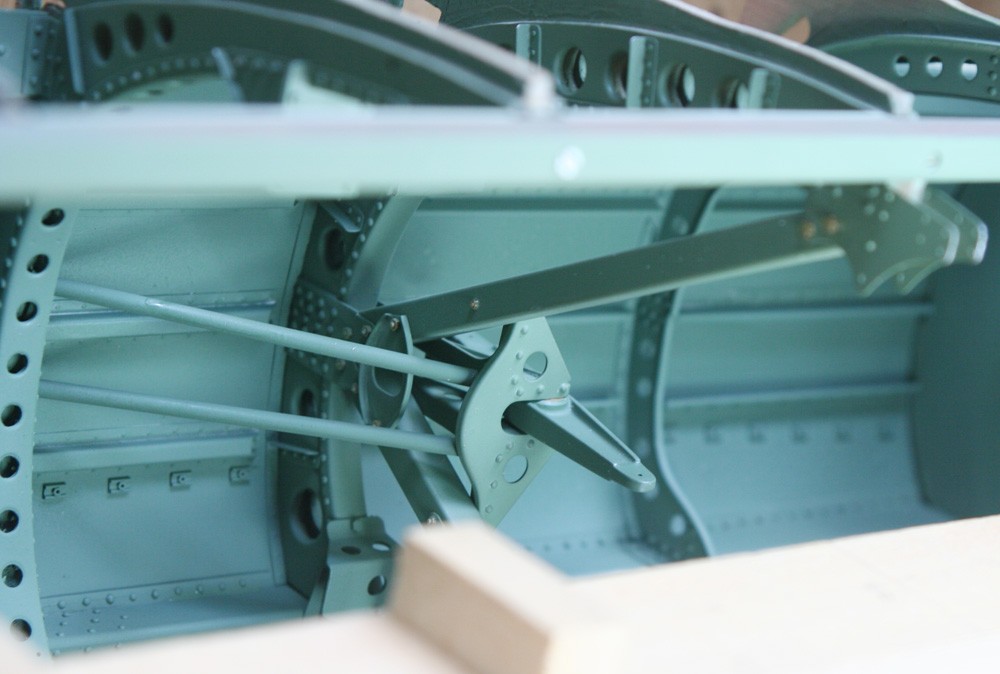

By July-August I began installing the fuselage belly skin between Frames 7 and 13, relieved that I had reached the first stage in the process of locking the potentially unstable open frame structure together.

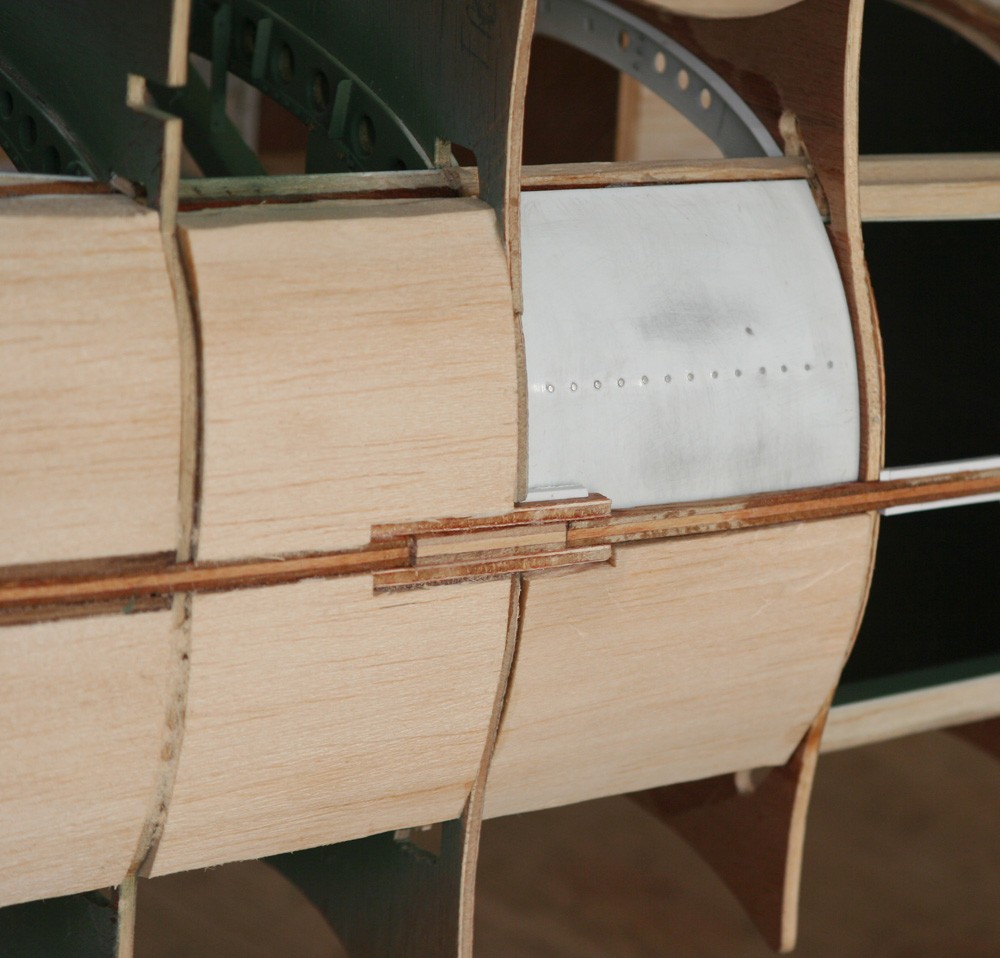

My strategy at this point rested on the skin surrounding the Spitfire’s cockpit being curved in one plane only, or very nearly so, a convenience that allowed me to make the recta-linear panels from flexible styrene sheet, each one glued to landings beneath the longerons and on either side of the fuselage frames. My intention was to reinforce the installed inner skin with an outer layer of 1/8 in. balsa sheet, thus providing considerable additional strength. As with the rest of the fuselage, the excess balsa would ultimately be carved and sanded back to the integral plywood cross-sections built into each main frame.

A complication, if it can be called that, arose with my decision to paint the skin panels prior to installation to avoid overspray of those internal elements already in situ. This, of course, necessitated each panel to be ‘pre-fabricated’ to include its stringers and whatever other detail that would be visible.

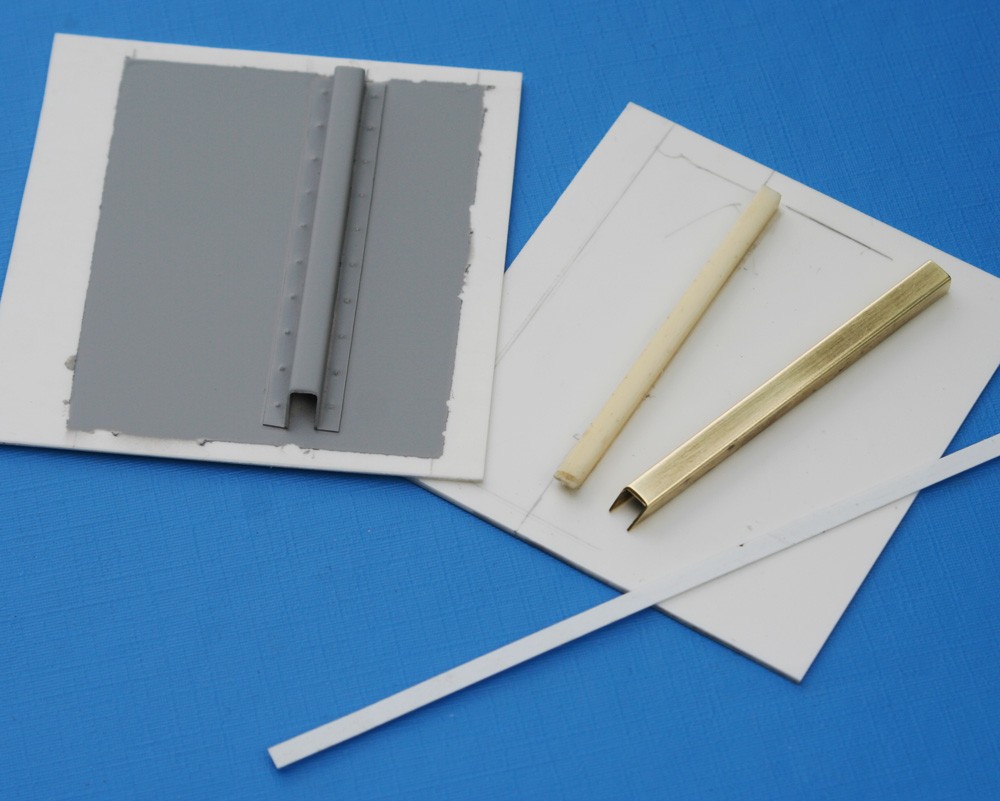

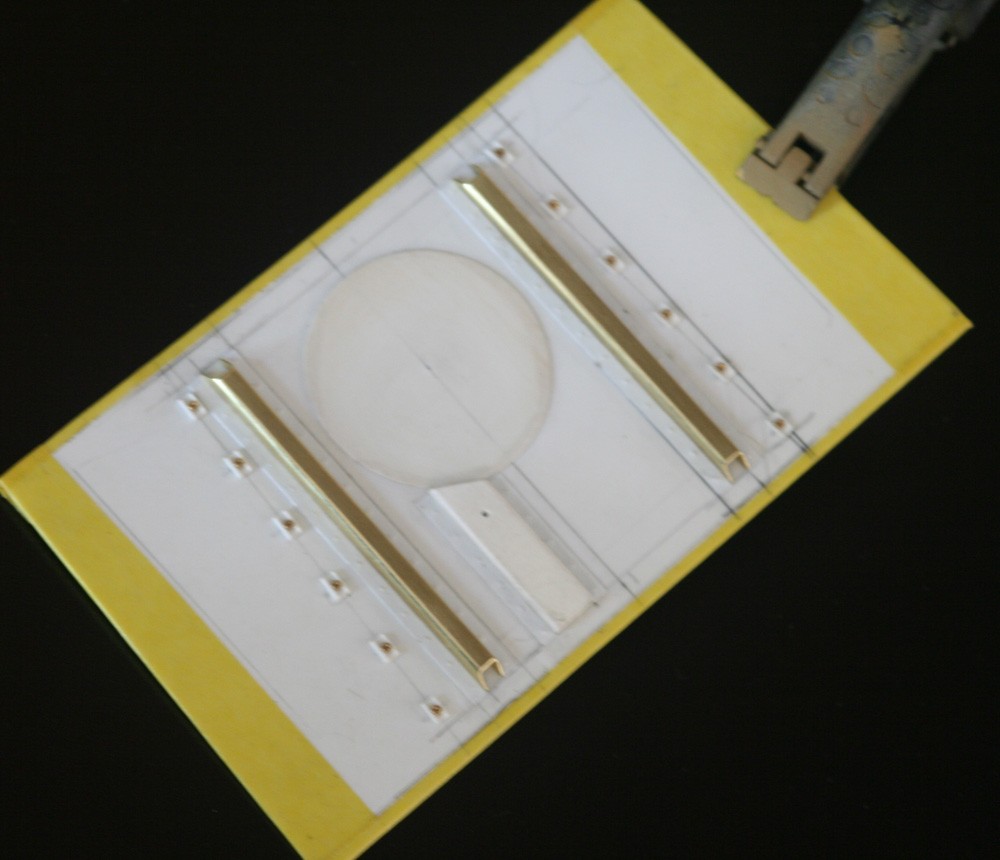

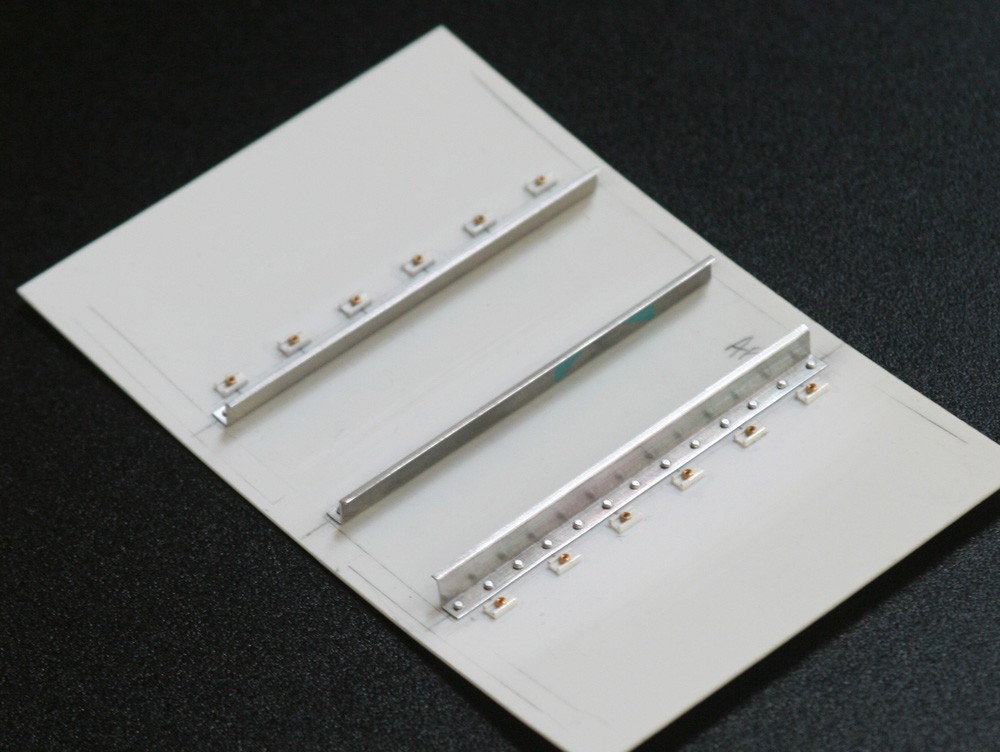

I formed the Z-section stiffeners from litho-plate, using sheet brass or steel guides of appropriate thickness to aid the folding and flange cutting. It would not have been overly hard to make the top-hat versions similarly. However, as in my previous Spitfire model, I decided to ‘cheat’ by using scale channel-section brass with flanking styrene strips to represent the flanges. Before installing anything, I marked the exact positions onto the skin panels and glued-on blanks of square-section styrene rod. Concealed within or under each stiffener, these would provide invisible yet robust fixings over which to glue them, creating load-bearing capability where needed for subsequent cockpit furnishings.

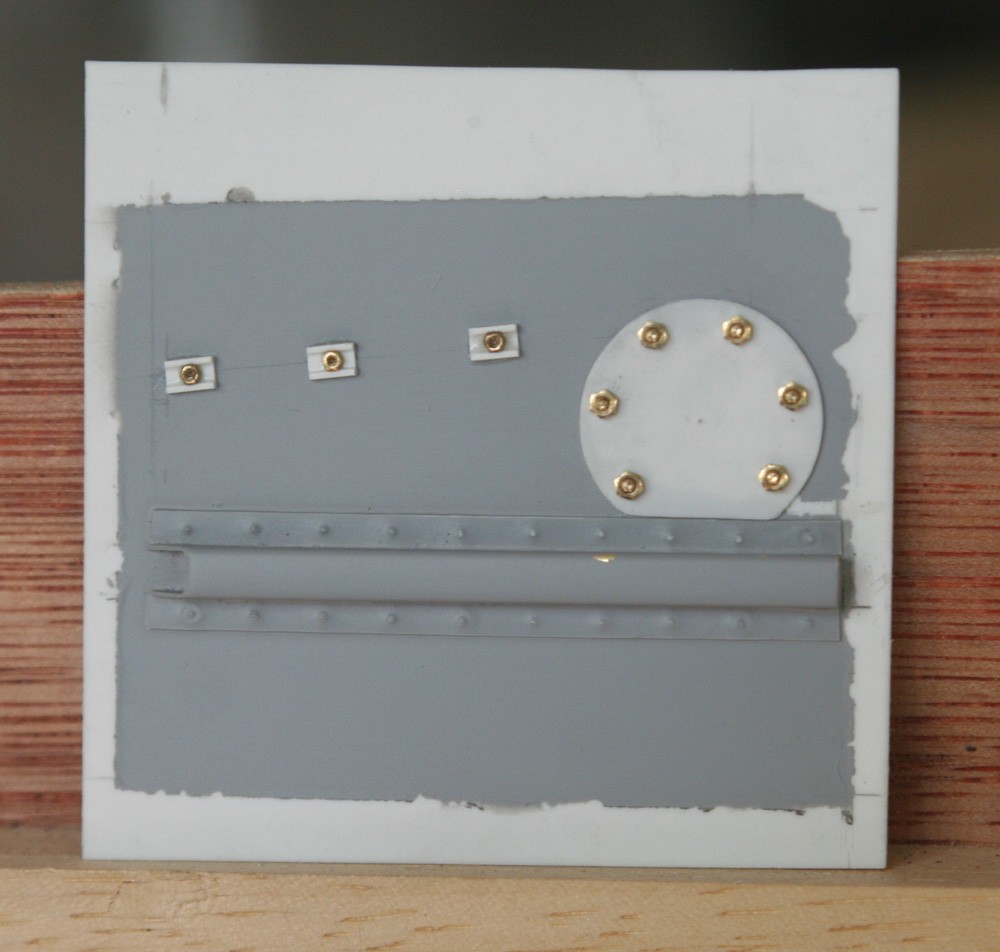

In reality, rivets and not ‘Superglue’ hold a Spitfire’s fuselage together, and here I confess to some experimentation: Working in the darkest, least visible recesses of the model, I firstly tried impressing rivet runs into the reverse side of the styrene ‘flanges’. I had used this well-tried technique before, and it works well when imitating domed rivets, be it in plastic or litho-plate. However, close inspection shows that most rivets as seen within the fuselage more resemble little flat cheeses. These, I decided, would be more accurately represented by the precisely squared-up shank ends of real aluminium rivets pressed into push-fit holes and secured by ultra-thin cyanoacrylate, judiciously applied from the reverse (balsawood) side. So, as work progressed, I exchanged my pointed scriber for a pin chuck, and steeled myself to drilling a very large number of tiny holes. The process also involved making a simple recessed ‘punch’ from telescoping brass rod and tube so that each rivet would be left proud by exactly the same amount. Yet the result was well worth the extra effort.

Inevitably, problems arose in those nooks and crannies where it was impossible to deploy a pin-chuck. So my next solution (perhaps yet more extreme) was to use thin styrene sheet and a punch and die set! Eva helped me tap out the tiny plastic discs, each of which I picked up on the point of a scalpel blade, anointed with the smallest wisp of glue and emplaced. Fortunately, the numbers needed were limited, for I do not think I could have kept that up for long! Unsurprisingly, after priming and painting the real rivets took the prize, although the punched out versions came a close second.

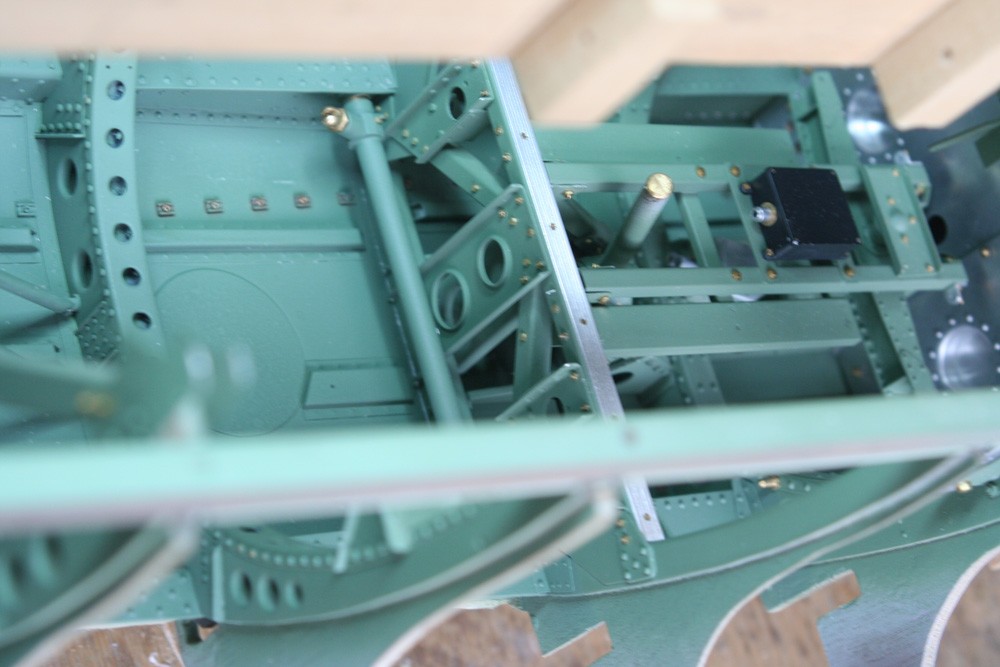

One further fine detail is worth mentioning: In the nether regions of a Spitfire’s cockpit, the numerous captive nuts for the wing root fairings are too prominent to ignore. My photograph speaks for itself of the simple ruse I used to imitate these. Going further would almost certainly have involved making a pattern for casting in resin, a path surly impractical given the large quantity of tiny copies required. My solution, while more suggestive than precise, works reasonably well, particularly after painting and weathering with a little rust coloured wash.