The Spitfire's spinner

Tuesday, 28th April, 2015

Mid-March and the first tentative signs of spring finally brought me out of a winter-long hibernation during which I had abandoned my workshop totally. Yet the thought of plunging straight back into the intricacies of the cockpit abandoned six months previously proved too much, so to ease into the swing I decided to tackle something very different – the spinner.

I rely on the specialist machinery and skills of Nick Bainbridge at Janus Metal Products for my nose cone blanks. But this time there was a problem. In his attempt to include the tricky nose cap recess which is often seen on the Mk IX, Nick had under represented the forward taper, with the result that the tip of the spinner was too wide even to correct on the lathe.

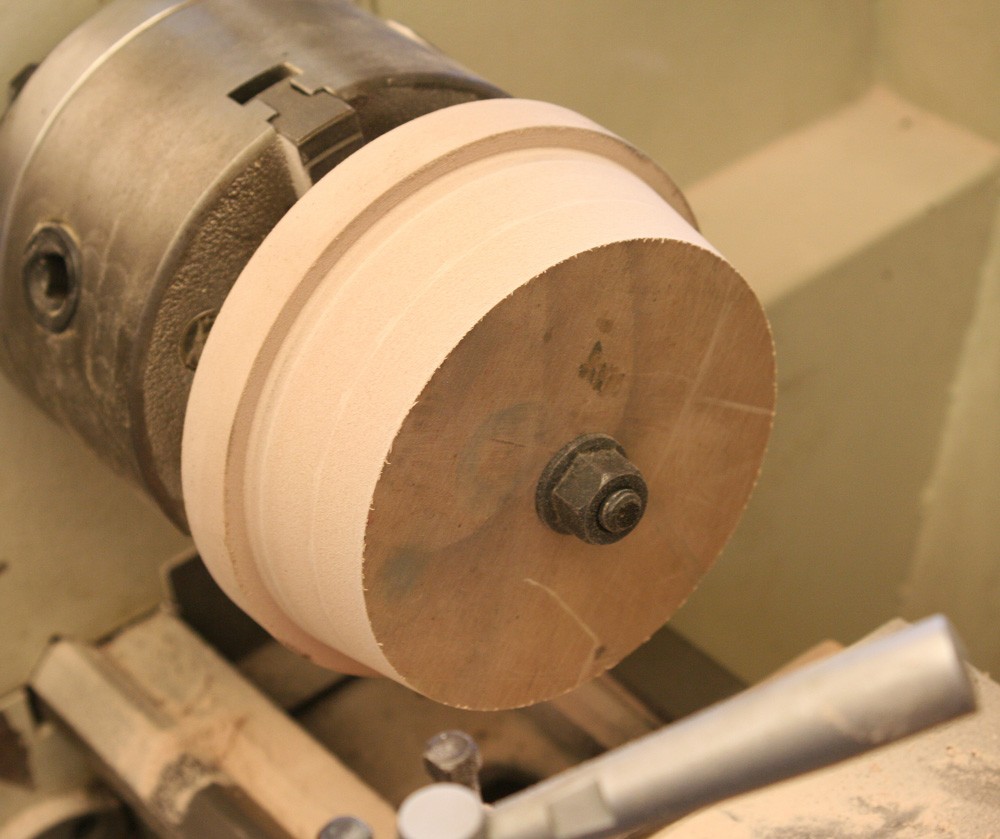

But more on this later; first I needed to divide the spun aluminium blank into its three component parts: skirt (back plate), main body and nose cone. I had totally wrecked one of my Mustang spinners when the parting tool on my lathe ‘dug in’, so this time I turned an especially sturdy and deep mandrel from high-density model board and attached the work-piece to it with four big screws. This time the machining went without a hitch.

I turned a back-plate from 5mm thick MDF, marked the 90 degree quadrants onto it and glued it into the skirt with cyanoacrylate. This provided a sturdy foundation.

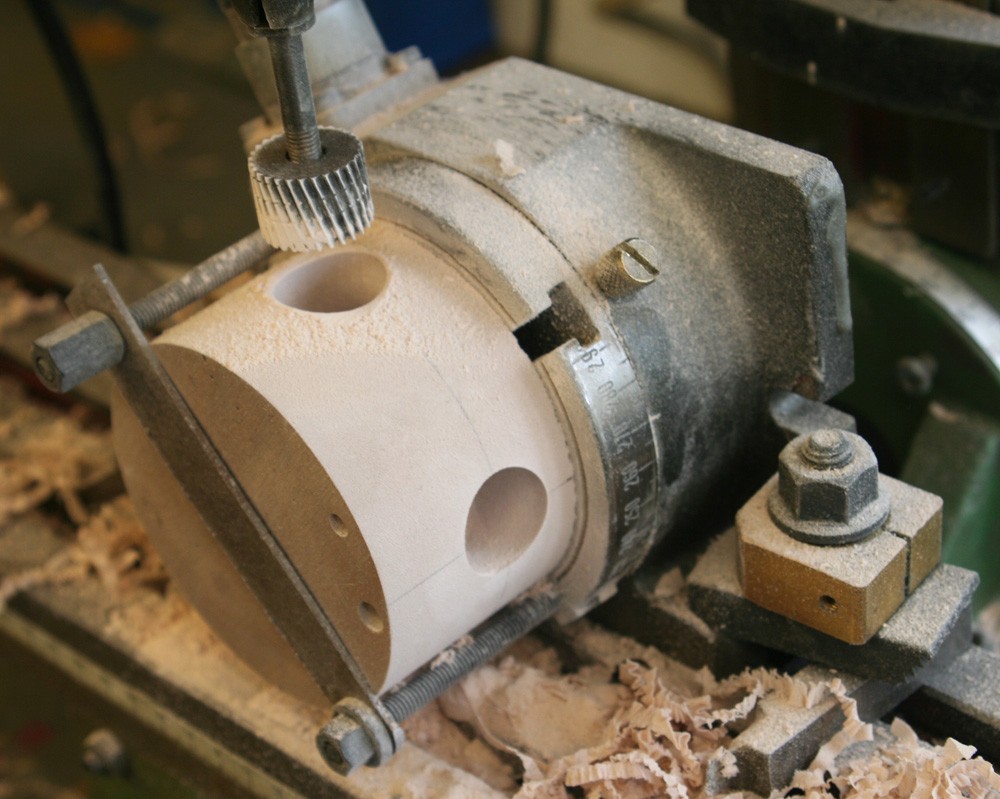

Next I marked and cut out the four arch-shaped apertures in the spinner body, being careful to retain the small C-shaped pieces, which would be needed later. Marking and drilling the many rivet holes took rather longer; and emplacing the alloy rivets longer still. I used snap head rivets glued from the reverse side so that their shanks, when cleaned down almost flush, represent the visible rivet-head diameters.

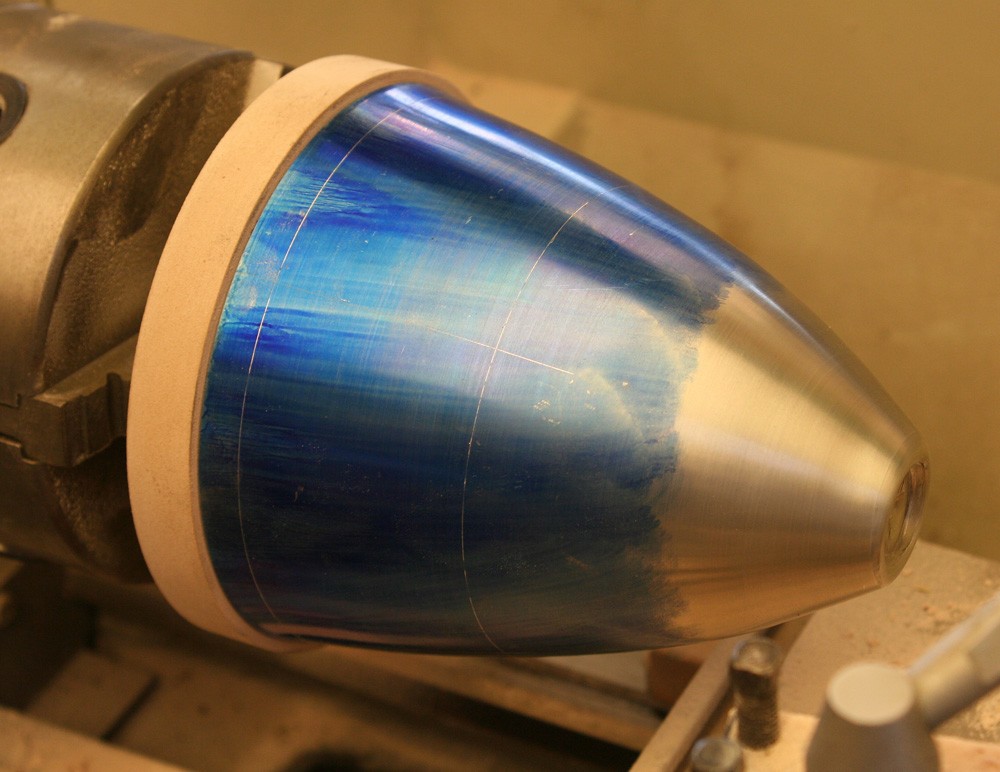

I had hoped there would be sufficient thickness of aluminium to be able to correct the errant taper on the lathe, but on cutting a template I saw immediately that this was not the case. I would have to discard the front part altogether, and for a replacement I decided to use resin.

As my photograph shows, I utilised one of the spare spinners as a mould in which to pour two-part resin around a suspended steel mandrel. Once the resin had hardened, I chucked the blank and set about turning it to the corrected profile using the template as a guide. I turned a recess into the base of the cone so that it would fit the internal diameter of the aluminium main body snugly.

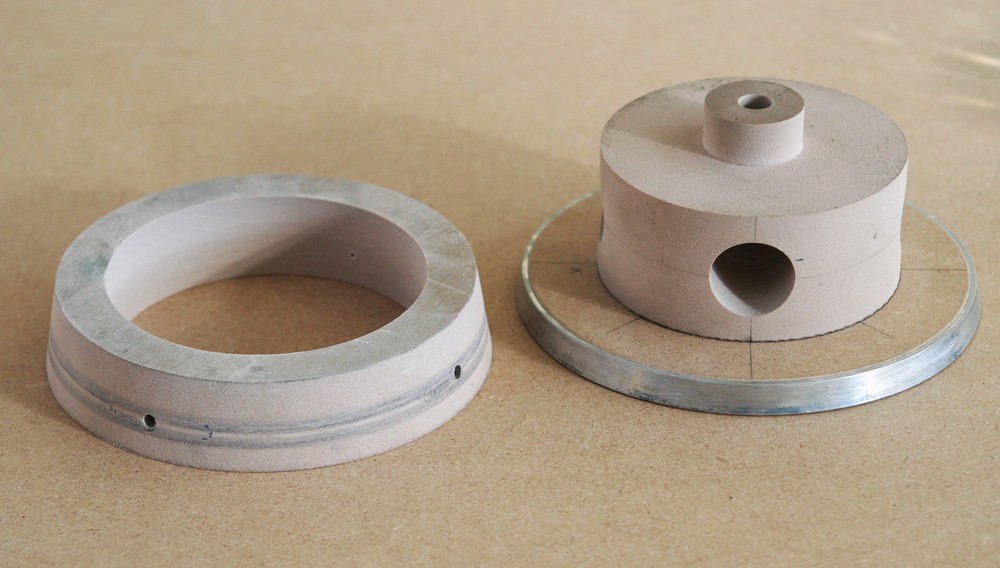

Hollowing out the resin (and removing the mandrel in the process) was a messy business, calling for power tools and a facemask, but at the end of it I was able to re-unite the spinner halves using two-part epoxy resin glue. A double row of rivets around the basal circumference of the resin part and a small nose cap turned from alloy completed the spinner outer shell. (The observant will note here I abandoned the recessed nose cap version in favour of one of the more straightforward alternatives.)

I made a simple propeller boss from high-density model board (which machines easily and well) and attached it the base plate with four countersunk screws. The model board mandrel originally used when machining the spinner blank came in handy again at this stage, since I was able to convert it on the lathe to act as the support for mounting the spinner body, which is attached by means of eight recessed screws self-tapped into the model board.

The final task was to clean up the four small C-shaped plates and glue them directly onto the model board support with cyanoacrylate.