Upper cockpit walls

Tuesday, 2nd June, 2015

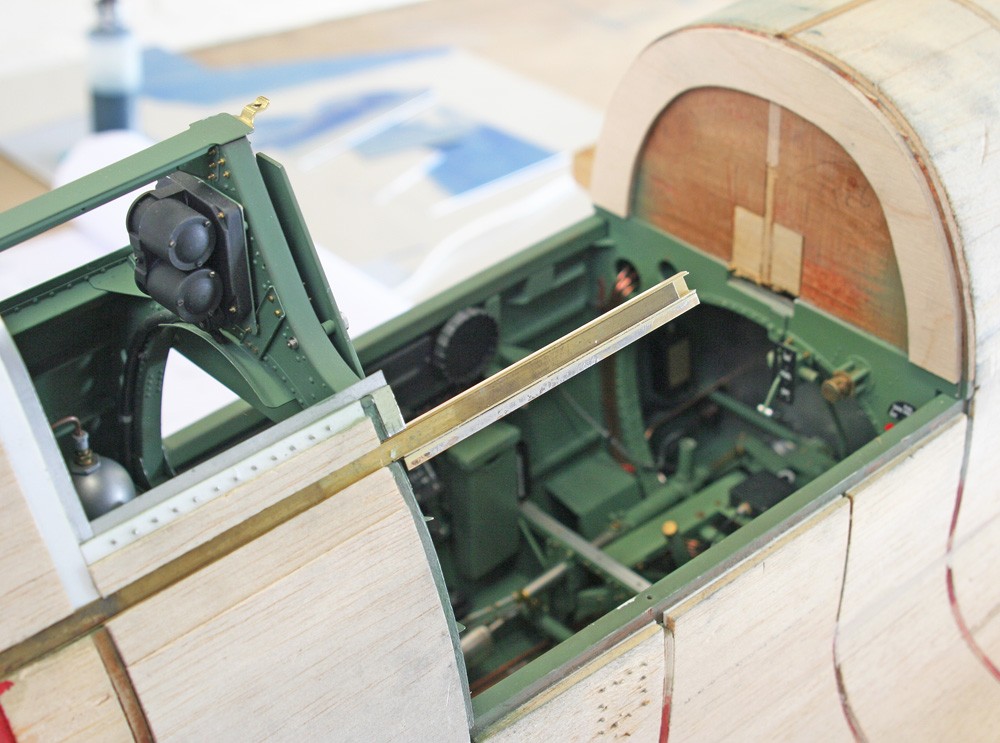

With the not insignificant exceptions of the engine and undercarriage control quadrants, joy stick, compass and pilot’s seat, the long process of fitting out the cockpit below the waist is nearing completion. And while there is clearly much yet to do, I have at last reached the stage where the upper cockpit sidewalls become a consideration.

The major structural criterion is that over a distance along the fuselage of almost nine inches from frames 8 to 11, there are no embedded ply cross sections, either to predicate the shape or impart strength and support. What goes there must be pre-formed closely to the upper fuselage shape. It must also be strong and rigid enough to retain its contours, while at the same time conveying the impression of lightness and scale, which in the real aircraft is the thickness of an alclad sheet! To compound the difficulties, the structure must be capable of being breached on the port side by the cockpit door.

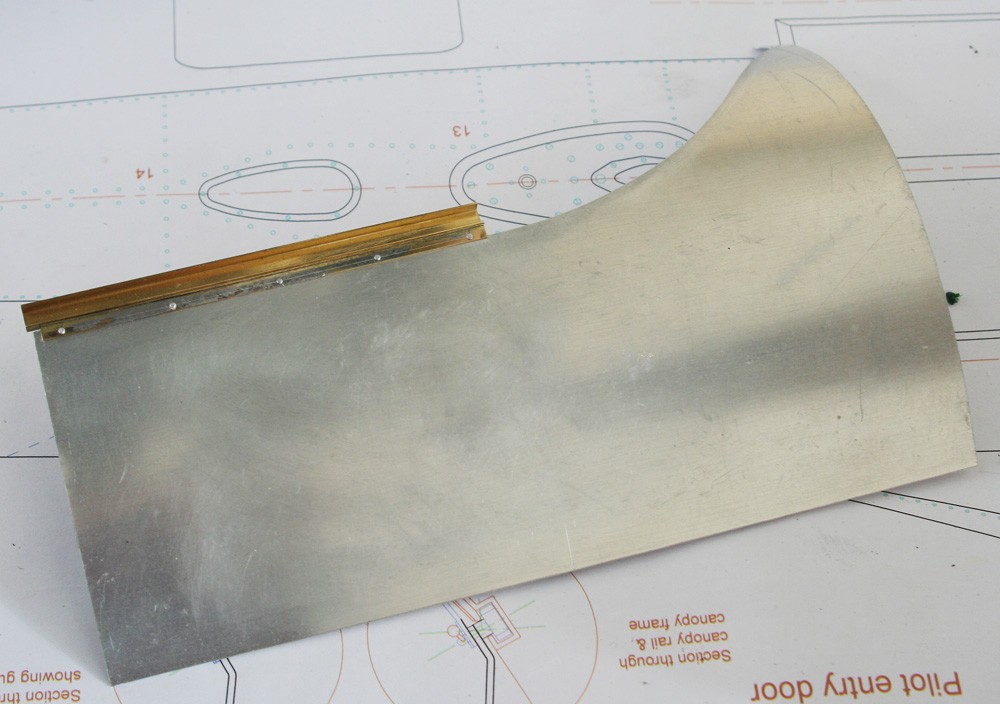

Initially, I envisaged a thin laminate comprising of 0.5mm alloy sandwiched between 0.5mm styrene and an outer skim layer of balsa. The un-annealed alloy is rigid enough of itself to take and hold the dorsal fuselage curvature, while being strengthened considerably by the additional layers. The plastic provides a pristine, ‘glue-friendly’ surface for subsequent interior detail and the soft outer balsa layer allows for easy sanding to the exact external fuselage continuum. Moreover, the final outer litho-plate skin will further strengthen the implanted structure, consolidating it into the overall fuselage architecture.

Paul Montforton’s drawings include ordinates for this part of the fuselage in the flat, so I was able to plot them onto a styrene template, thereby capturing in metal the graceful upward sweeping shape of the cockpit combing. The bending process is easier than it might seem: I used a large paint can as a former over which to create some arbitary but slightly over-tight curvature, then by offering the formed piece up to the model I carefully opened it out to the correct radius, making small, repeated adjustments until it fitted snugly to the fore-aft landings provided by the outer edges of frames 8 and 11. I made both the port and starboard sidewalls in this way, with the intention of cutting away the entry door at some later stage.

The canopy rails are fundamental to the upper cockpit walls. It will be recalled (August 29, 2014) that the rearward parts of these, where they pass beneath the fixed canopy, have already been installed, and that they are based on channel-section brass let into the balsa/ply substrate. The forward extensions are modified by a second telescoping channel section (to impart the correct thickness and external dimensions) and by soldered-on lengths of brass angle-section that provide a narrow, downward-orientated flange onto which the alloy sides are riveted (see Photo). Obviously, perfect fore-aft alignment of the rails is vital, and I achieved this by keeping both parts locked together during assembly by an internal brace of tight fitting rectangular brass.

Top-hat stiffeners

The next stage speaks eloquently of the ad hoc decision making that is so much a part of building models from scratch, and also of the mixed-materials approach that is fundamental to my brand of ‘model engineering’:

Firstly, I decided ‘on the hoof’ to omit the internal styrene skin layer from the proposed laminate, and instead to install the prominent vertical stiffeners directly onto the aluminium surface. I also glimpsed the feasibility of completing and painting the entire sidewall assembly, including all fixtures and fittings, prior to installation, thereby making access much easier – a significant departure from the modus operandi of my first Spitfire model.

Obviously, the first interior details to be added are the ‘top-hat’ stiffeners, which, in the real aircraft, are made as pressed alloy sections – not an easy option for the model maker. My work-around is a simple one: Each stiffener is formed from a length of square- or rectangular-section styrene* glued directly to the skin and flanked by narrow strips of litho-plate to represent the flanges.

The detail is finessed by carefully rounding off the outer corners of the styrene and by in-filling the sharp inner corners where litho-plate abuts with a run of thin cyanoacrylate, so as to create a slight radius. The use of real 1/32-in. allot snap head rivets at the correct pitch adds to the effect, particularly since it can create some very subtle dimples in the litho-plate flanges. Only in those few cases where a stiffener can be glimpsed end-on is the ruse detectable, yet even here you have to look hard to see it!

While time-consuming, the riveting of the flanges provides security for a job that would otherwise be reliant on cyanoacrylate glue. However, since the central styrene component is not riveted I took the precaution of scratching with the tip of a scalpel blade a deep key into the plastic and metal mating surfaces. Had I any lingering concerns, they were allayed when – because of an obvious misalignment – I attempted to prize the miscreant piece adrift in the jaws of my pliers!

*The top-hat stiffeners are well represented by square-section styrene, but scrutiny of the drawings show that two are a deeper Z-section with only one flange.