Engineering or 'sleight of hand'?

Wednesday, 11th September, 2013

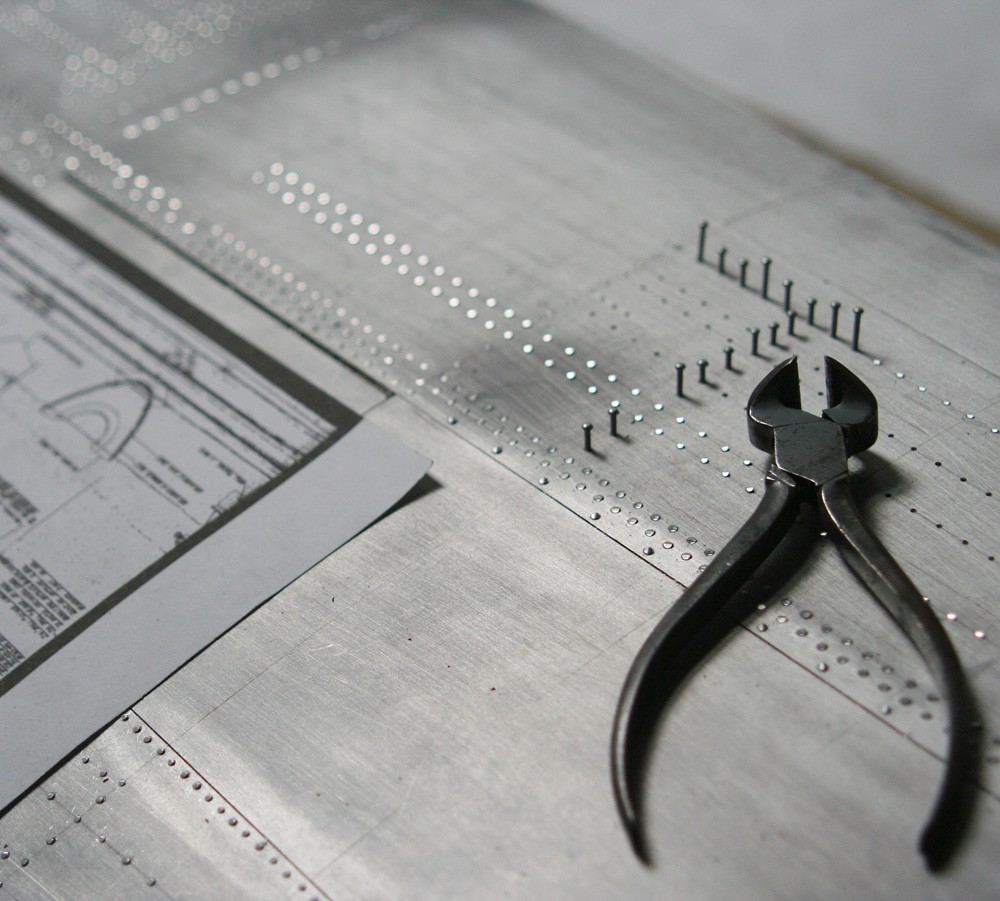

With the fire protecting bulkhead in place, the next logical step is to build and install Frames 8 to 12, as prelude to skinning the fuselage around the cockpit area up to the level of the waist longerons.

But before looking closer, a brief digression into the underlying methodologies that I have developed over some thirty years of making models, and how this fits into the hierarchy of ‘model engineering’.

In building my P-51D, I made the visible fuselage frames from aluminium, with the individual parts cut and assembled more or less directly as informed by the NAA production drawings. Likewise, I used aluminium for the longerons and all interior cockpit skin, with much reliance on mechanical fastenings in the form of tiny scale rivets and bolts. For both my Spitfires I chose to make the frames from a combination of plywood and styrene sheet, using litho plate for minor detail only. Why? The answer is simply because these materials seemed the most suited to this particular task.

I am not precious about the materials or methods I use, and while what I do is unquestionably ‘model making’, I do not pretend that it is ‘model engineering’! I choose materials that make the task at hand as easy and as practicable as possible, with the only condition that they must be stable, durable and appropriate to achieving the result that I seek. Large parts of my models most certainly are ‘engineered’ in the sense that the techniques used are those of the builders of model live steam locomotives. Metals of various types are turned, milled, drilled, ground, etc. to the required level of precision and held together with solders, brazes or with traditional mechanical fastenings. Elsewhere I rely more on the ways of the aero modeller, using plywood, balsawood, plastics and liberal applications of whatever glues are appropriate. And in the final analysis my models owe much to skills garnered from many years as a ‘basher’ of traditional plastic aircraft kits.

So while apparently faithful to the engineering drawings, the frames visible in the Spitfire’s cockpit are not what they seem beneath their paint. Yet by contrast the entire lower cockpit structure supporting the control column, rudder bar and heel boards is ‘engineered’ in metal from parts developed faithfully down to the last screw, bolt and washer from the Supermarine sheets. What is important is that taken overall the finished result looks ‘engineered’ in every sense; that what the eye sees is a faithful replica of the original, down to the look, feel, even patina of the finished construction. The ‘sleight of hand’ is to ensure that there is no discernible dislocation between ‘false’ engineering, as expressed, say, in the Spitfire’s fuselage frames or in my technique for riveting skin panels, to ‘true’ engineering employed in the turning of olio struts and landing wheels and axles.

My models are unashamedly an amalgam of methods and materials – under their metal skins is a wooden heart. Yet so long as the end result is robust, enduring and accurate, and above all convincing, and that the eye, however keen or insistent, is innocent of the subterfuge, I am content.